The status and protection of Local Wildlife Sites remain fragile, thankfully there is some protection through planning policy. Herts and Middlesex Wildlife Trust (HMWT) responds to any planning applications affecting LWS in Hertfordshire and Middlesex, and try to protect their ecological interest, with reference to The National Planning and Policy Framework (NPPF).

Local Wildlife Sites and the planning system explained

© Guy Edwardes/2020VISION

The NPPF contains the following policies which set the rules for assessing planning applications:

174. To protect and enhance biodiversity and geodiversity, plans should:

a) Identify, map and safeguard components of local wildlife-rich habitats and wider ecological networks, including the hierarchy of international, national and locally designated sites of importance for biodiversity

175. When determining planning applications, local planning authorities should apply the following principles:

a) if significant harm to biodiversity resulting from a development cannot be avoided (through locating on an alternative site with less harmful impacts), adequately mitigated, or, as a last resort, compensated for, then planning permission should be refused;

(c) Tim Hill

Some local authorities go even further with their policies in their local plans e.g. The East Herts Local Plan:

Policy NE1 International, National and Locally Designated Nature Conservation Sites

I. Development proposals, land use or activity (either individually or in combination with other developments) which are likely to have a detrimental impact which adversely affects the integrity of a designated site, will not be permitted unless it can be demonstrated that there are material considerations which clearly outweigh the need to safeguard the nature conservation value of the site, and any broader impacts on the international, national, or local network of nature conservation assets.

Many Local Wildlife Sites are further protected by other elements of planning policy

For example, several of our sites are also ancient woodlands or contain ancient trees. NPPF states:

c) development resulting in the loss or deterioration of irreplaceable habitats (such as ancient woodland and ancient or veteran trees) should be refused, unless there are wholly exceptional reasons and a suitable compensation strategy exists;

Whilst this protection is not absolute, it should steer development away from LWS in all but the most socially significant situations. It allows for an argument to be constructed to defend the site, supported by the precedent of planning decisions, which has a very good chance of being upheld by planning authorities and the planning inspectorate. LWSs represent the critical natural capital of the county and it is right that they receive this level of protection.

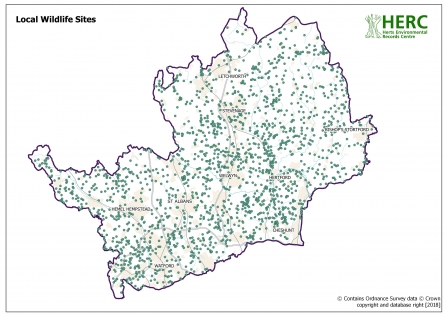

Local Wildlife Sites Map 2018

Why are Local Wildlife Sites so important for nature's recovery?

Even a Local Wildlife Site in poor condition has the capacity to recover at a far greater rate than a newly created habitat. They are not merely the plants that you see above ground but a complex matrix of fungi, invertebrates, molluscs, plants, birds, reptiles, amphibians and mammals. It is always better to try and conserve and enhance an existing LWS than it is to try and create new habitats.

Relationships between organisms can take many years to develop and once lost there is no guarantee that they can be rebuilt within a reasonable length of time. Studies have shown that the invertebrate diversity of a piece of high-quality grassland could take more than 100 years to be reproduced in a newly created grassland, and may not recover at all.

Whilst some invertebrates are very good at colonisation of new sites e.g. Water Boatman, there is a whole suite of specialists that have such poor mobility that they can only colonise a neighbouring site of similar habitat. These are some of the rarest and most threatened of our invertebrate fauna and extremely vulnerable to local extinction.

The loss of habitat change through neglect of just one LWS could result in the local extinction of one or multiple species.

Common spotted orchid (c) Josh Kubale

A wilder future for Local Wildlife Sites

This is why the stewardship of LWS is so important to the biodiversity of the county. Each one contributes to the nature network and helps to build a living landscape. This function may become an even more vital one in the future as the impact of the Environment Bill currently going through parliament becomes a compulsory part of planning decisions.

Although biodiversity net gain is currently a requirement of planning decisions, the mechanism by which it is measured is open to the judgement of Local Planning Authorities. This leads to inconsistent and subjective judgements in some areas, based on opinions, not data. Under this legislation, a standardised and repeatable way of measuring pre and post-development biodiversity value will be mandated – i.e. the Defra Biodiversity Metric; all planning decisions above householder will need to demonstrate a measurable net gain, which is an increase of 10% in habitat units. This means that the requirement to create new habitats will be much greater than currently.

The best way to create new habitat is to do so next to existing good habitat and to use material from an existing high-quality site e.g. a LWS. The Bill therefore could provide a new relevance for LWS together with higher levels of protection. Hopefully, this will see an incentive for the expansion of LWS and even provide funding for better management of existing sites where applicable.